High energy lasers were used to increase the impact velocity of the metal droplets, this ensures the droplets solidify in a disk-shaped form. Previous attempts at 3D printing metals involved the use of low laser energies, which resulted in less stable structures as the drops stayed spherical.

There are still some problems though, in the paper the researchers describe that while the high speed is required to achieve the desired drop shape, it also sometimes results in droplets landing on the subtrate next to the desired location.

3D printing of metals holds promise to create products like semiconductors, small cooling elements of connections between stacked chips.

A team of researchers from the University of Twente has found a way to 3D print structures of copper and gold, by stacking microscopically small metal droplets. These droplets are made by melting a thin metal film using a pulsed laser. Their work is published on Advanced Materials.

3D printing is a rapidly advancing field, that is sometimes referred to as the 'new cornerstone of the manufacturing industry'. However, at present, 3D printing is mostly limited to plastics. If metals could be used for 3D printing as well, this would open a wide new range of possibilities. Metals conduct electricity and heat very well, and they're very robust. Therefore, 3D printing in metals would allow manufacturing of entirely new devices and components, such as small cooling elements or connections between stacked chips in smartphones.

However, metals melt at a high temperature. This makes controlled deposition of metal droplets highly challenging. Thermally robust nozzles are required to process liquid metals, but these are hardly available. For small structures in particular (from 100 nanometres to 10 micrometres) no good solutions for this problem existed yet.

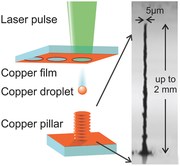

Researchers from FOM and the University of Twente now made a major step towards high-resolution metal printing. They used laser light to melt copper and gold into micrometre-sized droplets and deposited these in a controlled manner. In this method, a pulsed laser is focused on a thin metal film. that locally melts and deforms into a flying drop. The researchers then carefully position this drop onto a substrate. By repeating the process, a 3D structure is made. For example, the researchers stacked thousands of drops to form micro-pillars with a height of 2 millimetres and a diameter of 5 micrometres. They also printed vertical electrodes in a cavity, as well as lines of copper. In effect, virtually any shape can be printed by smartly choosing the location of the drop impact.

High energy

In this study, the researchers used a surprisingly high laser energy in comparison to earlier work, to increase the impact velocity of the metal droplets. When these fast droplets impact onto the substrate, they deform into a disk shape and solidify in that form. The disk shape is essential for a sturdy 3D print: it allows the researchers to firmly stack the droplets on top of each other. In previous attempts, physicists used low laser energies. This allowed them to print smaller drops, but the drops stayed spherical, which meant that a stack of solidified droplets was less stable.

In their article, the researchers explain which speed is required to achieve the desired drop shape. They had previously predicted this speed for different laser energies and materials. This means that the results can be readily translated to other metals as well.

One remaining problem is that the high laser energy also results in droplets landing on the substrate next to the desired location. At present this cannot be prevented. In future work the team will investigate this effect, to enable clean printing with metals, gels, pastas or extremely thick fluids.